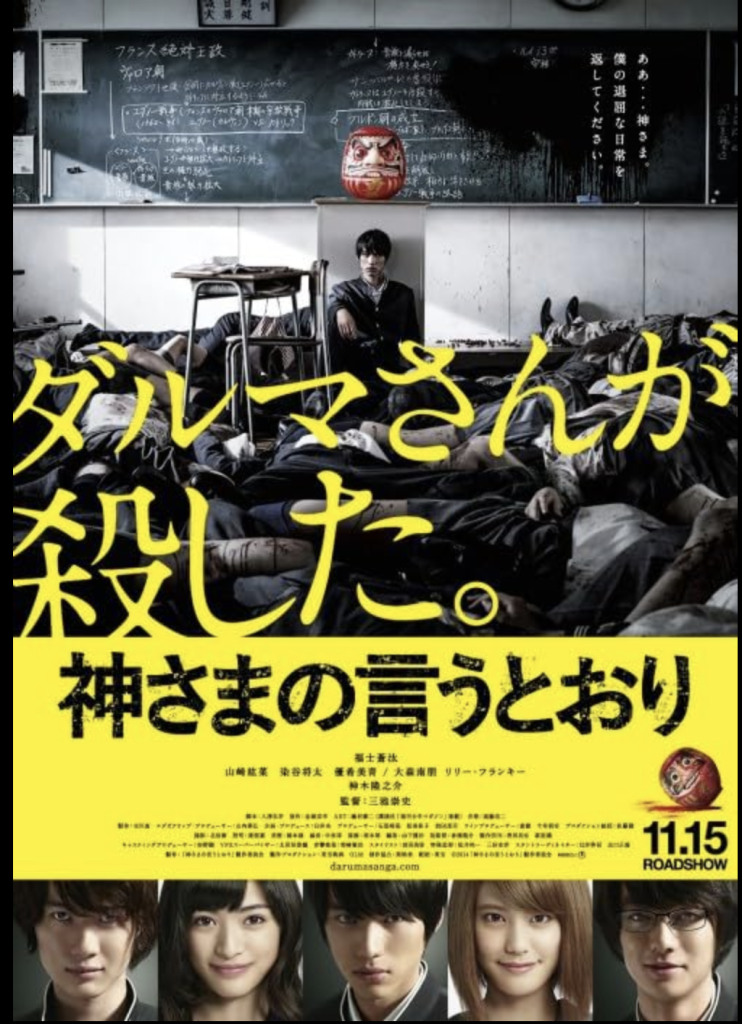

The Divine Playthings: A Sermon on Survival

It begins on a day like any other, with a thought that has echoed through the mind of every bored teenager: “God, my life is very boring.” This is the story of Takahata Shun, a boy who wished for something, anything, to break the monotony. His wish was granted, not by a benevolent god, but by a pantheon of cruel, playful deities who decided that humanity’s final purpose was to serve as their entertainment. This is not a story about saving the world; it’s about the terrifying realization that you are merely a pawn in a game you can’t comprehend, where the only rule is to survive until the next round begins.

The First Game: A Red Light, A Red Stain

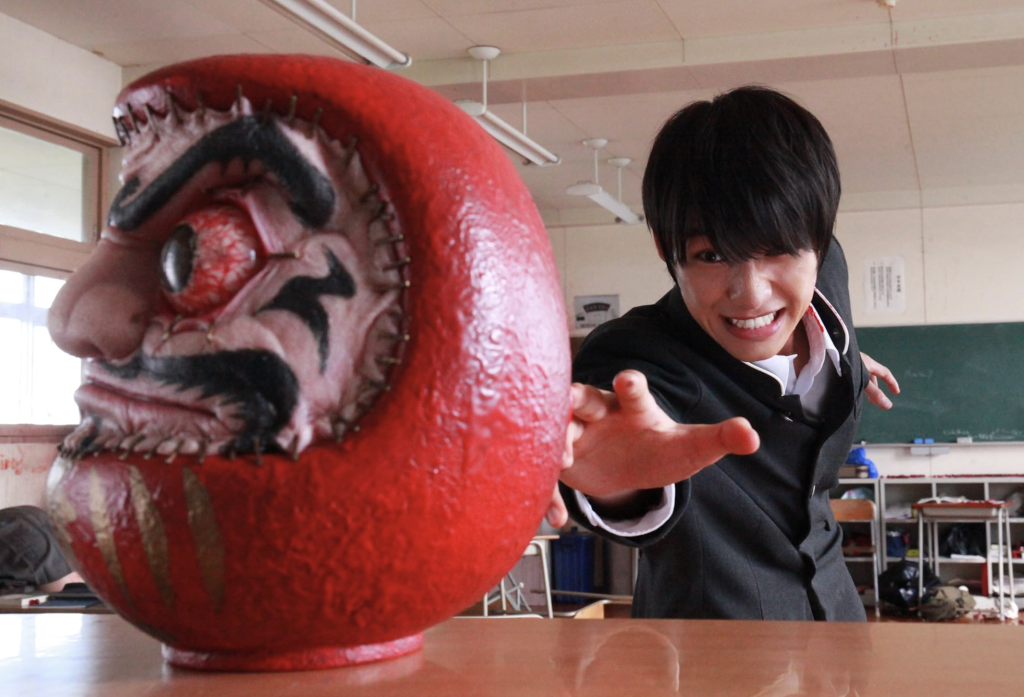

The divine intervention is not subtle. Without warning, the head of Shun’s teacher explodes, replaced by a grotesque, talking Daruma doll. It announces the first game: a deadly version of “Red Light, Green Light.” The rules are simple and absolute. When the Daruma sings “Daruma-san has come!” and turns its back, the students can run. When it turns around, anyone caught moving dies instantly, their bodies exploding into a shower of red marbles.

Panic erupts. Classmates are obliterated for a twitch, a stumble, a gasp. The classroom, once a symbol of tedious routine, becomes an abattoir. Amid the terror, Shun’s mind, sharpened by a lifetime of video games and a detached perspective on his own life, begins to see the pattern. This isn’t random chaos; it’s a game with a win condition. He realizes there is a button on the Daruma’s back that must be pressed to end the game. In a final, desperate gambit, he and his friend Satake coordinate a daring move, sacrificing Satake to propel Shun forward to press the button just as the timer hits zero. He survives. But he is the only one.

The Trials of the “Gods’ Children”

Shun is not alone for long. He and the survivors from other classrooms across Japan are transported to a massive, sterile cube floating high above the city. They are dubbed “God’s Children” by a terrified world watching below. Inside, they learn their ordeal is far from over. A series of deadly children’s games awaits them, each one hosted by a different, malevolent deity.

First, a giant Maneki Neko (a beckoning cat) forces them into a twisted game of basketball, devouring anyone who fails to score. Here, Shun is reunited with his childhood friend, Ichika, and encounters the enigmatic and dangerously intelligent Amaya Takeru, a fellow student who seems to revel in the bloodshed. Amaya finds the chaos beautiful, a world where the strong survive and the weak perish—a world, he claims, that Shun secretly desires as well.

The games grow progressively more sadistic and psychological. They must survive Kokeshi dolls who play “Kagome Kagome,” a game of blindfolded guessing where the price of a wrong answer is a laser to the head. Then, a towering polar bear, a Shirokuma, tests their honesty, demanding they uncover a liar among them, turning the survivors against one another in a brutal witch hunt. Through it all, Shun is forced to rely on his intellect, his empathy, and a growing will to live, not just for himself, but for Ichika and the others who look to him for hope. He becomes an unwilling leader, his mind the only weapon against the cruel whims of their captors.

The Final Game: An Unwinnable Choice

The final test is administered by a set of Matryoshka dolls. It is a simple game of “Kick the Can.” The survivors must hide while the “demon”—Amaya—searches for them. But there is a cruel twist: if a player is caught, they are imprisoned. If another player kicks the can to free them, that player will be killed in an explosion. It is a game designed to test the very nature of sacrifice.

Amaya, in his element, easily captures most of the survivors, leaving only Shun. In a moment of profound courage, Ichika sacrifices herself, kicking the can to free the others but dying in the process. Her final act gives Shun the chance to win, but it leaves him with an impossible choice: to survive is to validate Amaya’s brutal philosophy that only the selfishly strong deserve to live.

In a final, desperate confrontation, Shun uses his wits to outsmart Amaya and win the game. But the victory is hollow. He and Amaya are the only two left. They are then presented with their “reward”: popsicles. Each stick reveals their fate. Amaya’s reads “You die.” Shun’s reads “You live.” There was never a test of skill or worthiness. In the end, it was all down to luck.

There Is No God

As Shun stands alone, the sole survivor, the truth of his ordeal is revealed. He is not a “God’s Child.” He is a plaything. A homeless man who was living inside the cube appears and tells him, “There is no God.” The games were orchestrated by these beings for their own amusement. The cruelty, the loss, the sacrifice—it was all for nothing more than a spectacle.

The story ends with Shun, no longer bored, but broken. He has survived, but at the cost of everyone he cared about. He is left with the agonizing knowledge that his mundane, boring life was the true paradise, a gift he never appreciated until it was violently torn away. The tale serves as a dark sermon on the nature of fate, the cruelty of randomness, and the profound, painful irony of getting exactly what you wished for.